Mother had always been the family rock—the one who could withstand all life’s vicissitudes—but even granite could break apart under extreme pressure. This thought caused the pit of my stomach to roil, and not from the waves churning against our ship.

“Do you have the feeling this trip may be a mistake?” I asked Mycroft.

While I continued to stare over the ship’s railing, I caught him turn toward me from the corner of my eye. “The crossing is almost over. You’ll feel better when you get on dry land.”

I glared at him. “That’s not what I meant. Mother hasn’t been the same since Easter. Out of the blue, she announces we’re going to Paris while you’re still recovering from a gunshot wound. And she’d been distracted before that.”

My brother and I both inherited our mother’s usually composed nature. I’d rarely seen her rattled, but during our Easter holiday in London, she appeared preoccupied by matters she never expressed to either of us. At the time, I’d put it down to concern over my father’s efforts to invest in a business venture with an old school chum as well as Mycroft’s wounding at the hands of our kidnappers. Both, however, were now behind us. The investment had produced a modest return, and I saw no lingering problems related to Mycroft’s injury. All the same, we’d barely arrived home from school before she’d packed our trunks and shuffled us all off to Newhaven for the steamship ride to Dieppe.

“I do believe bringing the entire family is a ruse,” he said after his own inspection of the sea.

“Including Uncle Ernest in the trip did surprise me.” Her brother rarely left the estate or his workshop. “Perhaps she thinks it will do him some good. They report being happy growing up there.”

He glanced at the smoke trailing the ship. “If she was so happy there, why doesn’t she it?”

I ran through all the scenarios—from something as benign as a sudden bout of nostalgia to a fatal illness calling her back to see her French relatives one last time—and shook my head. “Without more information, I would only be speculating. You yourself have said that can be counterproductive. Whatever the reason, it has truly unnerved her.” I turned back to the ocean, seeking any indication of the coastline. “Whatever it is lies in Paris.”

Footsteps came toward us, and we both turned around. My mother’s maid Constance approached us. “Your mother asked me to inform you there’s tea in the cabin—if you want some.”

“I would,” Mycroft said. He turned to me one last time before he headed inside. “I suppose you’ll get your answers soon enough.”

My stomach gave another turn, but I didn’t voice the concern that came with the sensation—that the answer I sought might not be one I wanted to learn.

Constance stepped to the rail next to me and leaned her forearms against the top rung. We’d become friends when I’d returned home from school after my mother had been accused of murder. She’d been a great help to me in various adventures, and Mother had taken her under her wing to develop both her singing voice as well as her education. She was traveling with us as her lady’s maid.

I took a similar pose to hers against the rail, enjoying the ocean’s scent and letting the wind whip the hair from my face. Licking my lips, I savored the salt spray that seasoned them.

Letting out a soft “ooh,” she took in the white-foamed waves reaching as far as we could see under a clear, cerulean sky. I tried to see it from her point of view but couldn’t shake the anxiety remaining in my core.

She turned to me, and a loose tendril of her red hair whipped across her face. As much as the untidy strand annoyed me, I resisted the urge to tuck it behind her ear. Social etiquette dictated a young man wasn’t to have such contact with a young woman—especially one who was his mother’s maid.

To my relief, she moved the hair herself. “How long until we can see France?”

“The trip is supposed to take three hours. I’m not sure how long before we can see the coast.”

“Will it be as hot there as in England?”

“I hope not.”

The weather had been oppressive for more than a month now—with no rain to offer even temporary relief. The fields around Underbyrne, our family estate, held only dried, withered stalks, and the beehives my father had added to one back field hummed with a multitude of tiny wings fanning the hive to keep it cool.

“I can’t believe we’re goin’ to Paris,” she said, a joyful smile playing on her lips. “The farthest I’ve been from home was that trip to London with your family. Now Paris. What’s it like?”

I shrugged. “I’ve only seen pictures, but I think it will be a lot like London in some ways.”

She shifted back around to face the ocean. “Well, I’m not goin’ to waste a minute not enjoyin’ it. Like this boat ride. I ain’t—er, haven’t—been on anything this big in my life. It’s like a floatin’ hotel. Goin’ to drink me some tea on a boat—”

“Ship.” She squinted a question at me. “It’s a ship. Don’t let the crew hear you call it a boat. Ships are bigger.”

“Well, I’m goin’ to get me some tea on this ship so’s I can tell my brothers and sisters I had me some.”

She flounced off, leaving me to ponder exactly what lay ahead.

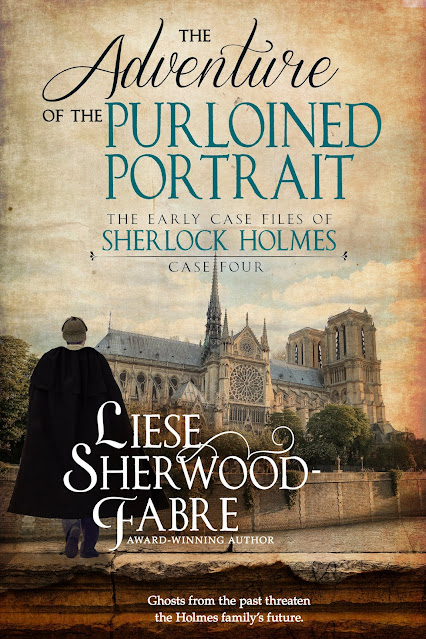

Liese Sherwood-Fabre knew she was destined to write when she got an A+ in the second grade for her story about Dick, Jane, and Sally’s ruined picnic. After obtaining her PhD, she joined the federal government and worked and lived internationally for more than fifteen years. Returning to the states, she seriously pursued her writing career, garnering such awards as a finalist in RWA’s Golden Heart contest and a Pushcart Prize nomination. A recognized Sherlockian scholar, her essays have appeared in newsletters, the Baker Street Journal, and Canadian Holmes. She has recently turned this passion into a series on a young Sherlock Holmes. The Adventure of the Murdered Midwife, the first book in The Early Case Files of Sherlock Holmes series, was the CIBA Mystery and Mayhem 2020 first-place winner. Publishers Weekly has described her third book in the series, The Adventure of the Deceased Scholar, as “the best plot yet.” The next book, “The Adventure of the Purloined Portrait,” is due out in early 2022.

Liese Sherwood-Fabre knew she was destined to write when she got an A+ in the second grade for her story about Dick, Jane, and Sally’s ruined picnic. After obtaining her PhD, she joined the federal government and worked and lived internationally for more than fifteen years. Returning to the states, she seriously pursued her writing career, garnering such awards as a finalist in RWA’s Golden Heart contest and a Pushcart Prize nomination. A recognized Sherlockian scholar, her essays have appeared in newsletters, the Baker Street Journal, and Canadian Holmes. She has recently turned this passion into a series on a young Sherlock Holmes. The Adventure of the Murdered Midwife, the first book in The Early Case Files of Sherlock Holmes series, was the CIBA Mystery and Mayhem 2020 first-place winner. Publishers Weekly has described her third book in the series, The Adventure of the Deceased Scholar, as “the best plot yet.” The next book, “The Adventure of the Purloined Portrait,” is due out in early 2022.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.